World Parrot Day- The important role of parrots across cultures

- Patricia Pillay

- May 31, 2024

- 5 min read

Pictured below are Rose-ringed Parakeets (or Indian ringneck parrots) that I was fortunate to snap on a hot afternoon in my mother's hometown Surat in Gujarat while visiting my Grandmother. These cheeky parrots are not shy and flock to the apartment complex and can be found chattering away near the temples close to my grandmother's house! They are well adapted to urban life often perched on the side of building walls. Throughout Indian history, these birds have been highly regarded in society and admired for their striking plumage and characteristics.

Photos taken by Patricia in Surat Gujarat.

To celebrate World Parrot Day I wanted to share my most recent publication (which is open-access, meaning freely available to read!) that looks at human-bird interactions in East Polynesia! Across the world, parrots play a significant role in cultural identity and I have been fascinated by the remarkable role they have in Pacific history. Oceania has some of the world’s most threatened taxa of birds, such as parrots, of which almost half (47%) of the extant species are threatened with extinction (Olah et al., 2018). Many species are culturally significant to communities across Oceania, not just as a food source but also as pets, prized for their feathers used in personal adornment, and feature significantly in local knowledge. My most recent paper includes several lines of evidence compiled from museum records, historical sources, and oral knowledge from local Marquesan peoples.

Feather adornment is a prominent symbol of status in the Marquesas Islands and exhibits exquisite craftsmanship featuring a wide range of colours that were used across Tonga, the Marquesas, the Cook Islands, and beyond. One of the most sought-after items was red feathers that were traded and exchanged across Oceania. Feathers were seen as highly valued raw materials of wealth in many Pacific Island societies and were traded across vast regions and with European settlers for other goods. Prestige items such as feather cloaks and headdresses reinforced chiefly status and mana as well as asserting genealogical and spiritual connections to their divine ancestors. Many of these feathered ornaments now lie in museums around the world, acquired through a variety of means from expeditions and trade during the early 18th-20th centuries. In the Marquesas, feather headdresses were particularly associated with items of wealth and were a distinctive decorative item adorned by Marquesan chiefs worn only for specific ceremonies and occasions.

Multiple Polynesian oral histories highlight the re-occurring theme of red feathers as an item of exchange. One instance is the Marquesan oral legend of the hero Aka’s journey for red parrot feathers to the Cook Islands (Handy, 1930), which indicate Marquesan-Cook Island connections. German physicist and ethnologist Von den Steinen (1988) also describes the manu ku’a bird in the oral histories as a coconut shell-eating red parrot and reaffirms that in historical times apparently no living person had observed such a bird. Several red-feathered parrot species across Near and Remote Oceania are confirmed to have been utilised in Polynesian feather trade and exchange (Kahn et al., 2022; Torrente, 2012). Within the French Polynesian region, such as in the Society Islands, feathers - particularly red - were high-ranking wealth and prestige items (see Kahn et al., 2022).

In the Marquesas, the manu ku'a (red bird) was described as having a close resemblance to the Hawaiian honeycreeper or ‘I’iwi, suggesting it was red (Brigham, 1903). Red is a significant colour across Polynesian societies as a symbol of divinity, beauty, and perfection (Elbert,1941). The pa’e ku’a headdress is typically associated with mana and prestige. This type of headdress is described as an ‘ancient’ form and is consistently associated with the extinct manu ku’a bird that appears in Marquesan oral histories. Headdresses associated with high-ranking individuals, such as pae ku'a, uhikana and ta’avaha, required significant time and resource investment for manufacture. Specific environmental knowledge would be required to know when and where to obtain certain feathers from birds and where to catch them. Oral histories also note the deliberate plucking of certain feathers and generally allowing these birds to be released. Such decisions indicate a form of resource management in terms of how a bird was used for manufacturing certain objects.

I was lucky enough to learn more about some of the amazing Parrots in the Marquesas Islands from Marquesan Anthropologist Edgar Tetahiotupa who shared with me the following:

"The Manu ku’a (translates to red bird), has a special place in Marquesan culture. One of the personal adornment items in Marquesan culture is the headdress called pa’e ku’a, which includes parrot feathers. We have in Marquesas, the bird called Kuku (Ptilinopus dupetithouarsii or White-Capped Fruit Dove). When I compare the feathers of the pa’e ku’a with the feathers of the Kuku and the Vini ‘ura, I think the feathers of the pa’e ku’a is closed to those of the vini ‘ura (Vini kuhlii, or Rimatara Lorikeet). But, now we have no vini ‘ura (or vini ku’a) in Marqueas Islands, but we have the word ku’a in pa’e ku’a. So, it would be interesting to know if we have had vini ku’a in ancient time Marquesas."

Currently, the only Vini present in the Marquesas Islands is the beautiful Vini ultramarina (pictured below). This ultramarine lorikeet resides on Ua Huka and is classed as Critically Endangered under the IUCN Red List due to its restricted range although there is ongoing conservation efforts to reintroduce this species on other islands in the Archipelago.

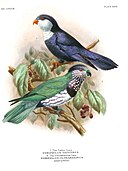

Left to Right. Image1: Top: Vini Peruviana vini (Society), vini (Tahiti), vini pa tea (adults/Tahiti), vini pa uri (subadults/Tahiti)). Bottom: Vini Ultramarina (Pihiti -Ua Pou, Nuku Hiva, pihitikua -Nuku Hiva.

Image 2: Vini Kuhlii .

Image 3: Vini australis- Blue Crowned Lorikeet (Segavao (Samoa), Hengehenga (Tonga)). Names from Manu SOP https://www.manu.pf/?lang=en. Image source: John Gerrard Keulemans, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The term manu ku’a (red bird) is a shared term with other variants across Oceania. The general term kura or kula also refers to the sacred, crimson bird of the gods, called kura mea and kura hake at Tatakoto, and across many islands is attributed to a parakeet. Another example is in Fangatau chants from the Tumotus such as vivivini te tangi o te kura. Another example is in Tahiti, where ‘ura refers to Vini- a genus of lorikeet. The similarity across Polynesian languages for red feathered bird might not surprise you considering the multiple connections between islands. Terms like manu ku'a, kula, kura for example also highlights the role of etymology in tracking the importance of names assignment to different taxa. Also, multiple birds can hold the same term. The term manu ku’a also refers to other species for Marquesan adornment, including the Red-Tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon rubricauda) and Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). The shared term between taxa suggests some use of alternative species fulfilling certain functions that the extinct manu ku’a might have occupied in the past. The overall rarity of the pae ku’a headdress, and the fact that it was no longer in manufacture by the time missionaries and ethnologists were in the Marquesas, indicates the difficulty in procuring the specific coloured feathers and knowledge required for manufacture.

There is a strong call for archaeologists, anthropologists, and specialists working in natural sciences to consult multiple knowledge sources when investigating the long-time record of human-animal relationships. This in turn can assist in tackling current issues and questions on preserving or restoring biodiversity, including species reintroductions. Integrating a sensitive cultural perspective with conservation methods is essential for the ongoing protection and cultural management of birds like parrots!

If you would like to read more, and find out about some of the other birds I looked at alongside the remarkable parrots you can access my full paper only in the Journal Archaeology in Oceania! All citations from above are included in the Reference List of the article.

Comments